Lt. Colonel Kenneth Christian Rowe (1916-2009), was the youngest of the six children of William and Christine Toellner Rowe of 513 Third Street in Boonville.

Kenneth was called into the U.S. Army in January 1942, while a student at the University of Missouri. After transferring to the Army Air Corps he was trained as a Navigator-Bombardier to serve with the 12th Air Force, 57th Bomb Wing, 340th Bombardment Group, 488th B-25 Bomb Squadron. Little had he known when he left Boonville that he would be joining one of the most storied units of World War II, and would play a decisive role in defeating the German war machine in Europe.

| |

[Then] Major Kenneth C. Rowe in 1964, after he had returned from his GEEIA posting in Germany to March Air Force Base in California.

1st Lieutenant Kenneth C. Rowe (left) and brother W.T. Rowe in front of their home at 1001 Locust Street in Boonville in 1945, after both had returned from the war.

Alesan (Alesani) airfield on Corsica, home to the 340th Bombardment Group ('The Best Damn Group There Is') from August 1944 to April 1945. Alesan was an ALG ('Advanced Landing Ground', with prefabricated buildings that were quickly assembled and disassembled, and little in the way of creature comfort.

Alesan had separate tent cities for officers and enlisted men until October 1944, when officers acquired trailers. Heavy winter rains meant damp, cold living conditions and frequent slogging through mud.

Flight crews leaving the mission briefing room, then preparing for takeoff on Alesan's hard dirt runway.

Bombardier and Norden bombsight in the exposed nose cone of the B-25. Nerves of steel were required to control the plane and aim the payload while only thin glass separated one from the violence outside.

(Click to enlarge)

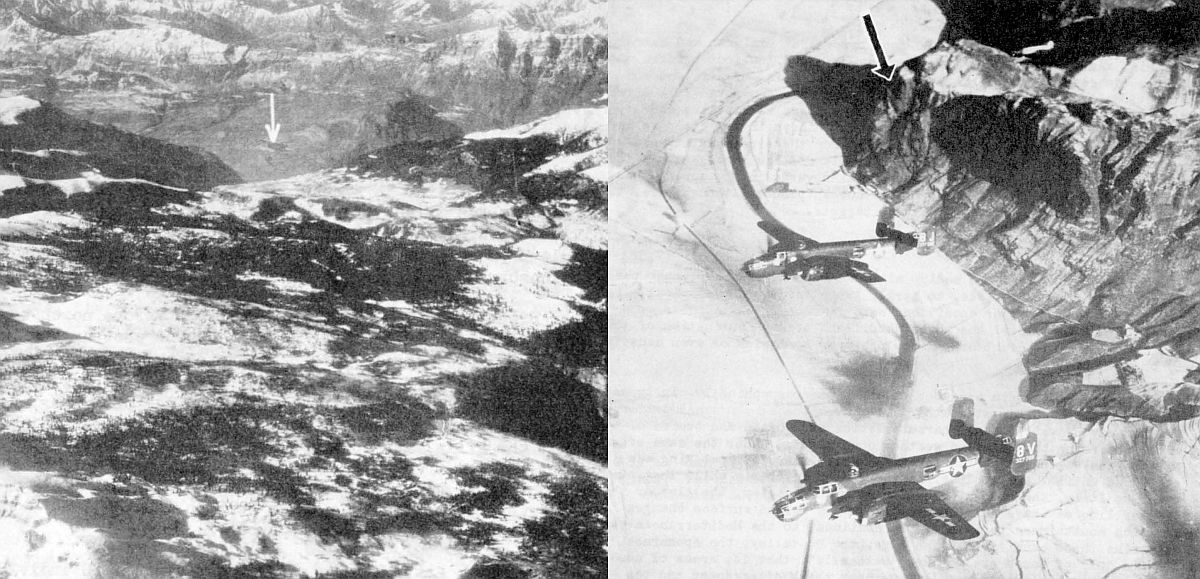

Terrain and light played major roles in target visibility. At left high cliffs hide the target, which will not be visible until late in the bomb run; the arrow shows its location. At right, dark pre-noon shadows near the cliffs obscure the target, indicated by the arrow.

Crews for the 05 April mission to San Michele All' Adige, the Brenner Campaign's most-bombed target with 823 sorties, a hundred more than to Rovereto and Lavis. On return from this mission, Rowe was promoted to 1st Lieutenant. (Click for the full two-box mission roster.)

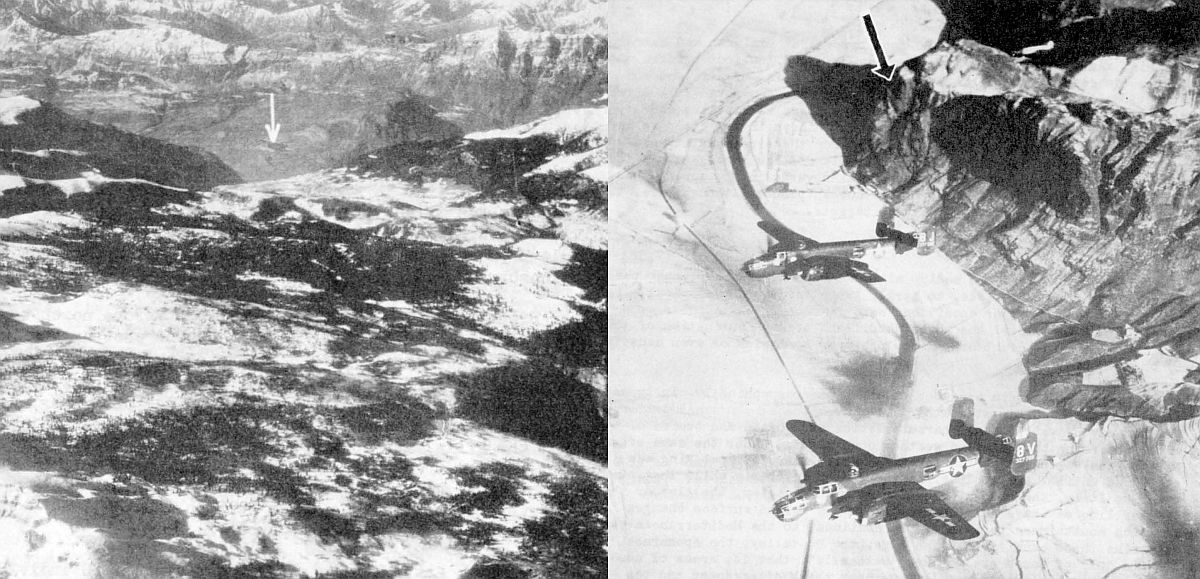

Missions usually flew in 'boxes' of six planes, closely spaced for effective bomb patterns and fighter defense. However, flak from German 88s was thus more easily concentrated. On 'hot' missions with heavy flak, most of the returning planes were often severely 'holed'.

The B-25 at top was fatally holed in the left wing, but made it to Switzerland before crashing. The crew parachuted to safety. Below, flak ripped off a third of the right stabilizer. The plane made it back to Alesan, the tail gunner in severe shock but still intact.

Rail-mounted mobile 88mm anti-aircraft units which could be easily relocated, and fixed installations.

'Flak map' showing in red heavily-defended areas crews should avoid if at all possible; note that the Brenner Pass (vertical at top center) is all red.

There was little room for error in the closely-spaced flight boxes. On 21 January 1945 almost half of the rear assembly of '8P' was cut away by the left propeller of '8U' below, buffeted upward by turbulence. Miraculously, '8P' made it back to Alesan, but the tail gunner didn't. This event was prominent in Heller's Catch-22.

Target summary map of the Brenner Pass Campaign (right-click to open or save a larger version).

Kenneth Rowe's sketch of an ivory-billed woodpecker, similar to the local flora and fauna sketches he made while off-duty on Corsica.

Cover of Kenneth Rowe's 2004 157-page Flora and Fauna of a Village (Air Force Village West, San Bernadino, California), his last collection of sketches.

|

The 488th Bomb Squadron was activated on August 20th, 1942, specifically to fly the B-25 “Mitchell” medium bomber, which on April 18 of that year had been made famous by General Jimmy Doolittle’s raid on Tokyo from the aircraft carrier Hornet. The B-25 had advantages of speed, maneuverability, range and durability over other Allied bombers, and also had the capacity to strafe. Thus it was chosen as the principal tactical bomber in the Mediterranean theater, with the assignment between April 1943 to April 1945 of disrupting German supply and troop logistics in the campaigns in Italy and southern France.

From August 1944 through April 1945 the 488th and the other three squadrons of the 340th Bombardment Group operated from Alesan airfield, a prefabricated 'Advanced Landing Ground' on the northeastern coast of Corsica.

The B-25J aircraft flown by Rowe and the other crews of the 488th were equipped with the Norden bombsight, originally designed for high-altitude missions. The crews of the 488th soon got a more specific task: they were to adapt the Norden to low-altitude precision bombing of highly protected critical targets.

From August through November 1944, in support of the post-D-Day Allied advance into Western Europe, the 488th primarily hit key German logistics targets in Southern France and Northern Italy, including Avignon, Bologna, and Ferrara. These missions were highly effective in disrupting enemy mobility and supply, although attacking such heavily-defended targets took a toll on both aircraft and crews.

However, the most significant, and dangerous, role the 488th played, together with its three companion squadrons in the 340th Bombardment Group (the 486th, 487th and 489th), was during the campaign in the Brenner Pass of Northern Italy between November 1944 and April 1945. In its drive from Sicily up through the Italian mainland, Allied land forces had been unable to penetrate the highly-fortified German “Gothic Line,” which crossed the Northern Apennines from La Spezia on the Ligurian Sea to Rimini on the Adriatic.

German forces were being supplied some 24,000 tons of material daily, six times their minimum daily need. Up to 72 trains from Munich or Augsburg were arriving every 30 minutes along a dual-track electrified rail line through the narrow, twisting pass, a 59-mile-long corridor of 60 bridges and 22 tunnels which cut through the Apennines from Brennaro, on the border of Italy and Austria, through Bolzano and Trento to Verona and Bologna.

With this ability to reinforce and replenish its forces, the Germans could continue their war of attrition along the Gothic Line almost indefinitely.

The pass was also the only German escape route from Italy. Denying the pass to the enemy would seal the fate of the German army in Italy.

The task of the 488th seemed simple enough: to exploit the B-25J’s speed and maneuverability and the accuracy of the Norden bombsight by flying from their base at Alesan [Alesani in Italian] Airfield on the island of Corsica across northern Italy to eliminate the bridges and tunnels of the Brenner Pass one by one, so German forces could not be reinforced, supplied or evacuated. Attrition would then force their surrender. Accomplishing that task, however, proved far from simple.

While roughly one third of the missions were “milk runs,” encountering little or no resistance, these were primarily to less-critical targets that were easy to hit. But they were also easy to rebuild, and therefore less defended. The other two thirds of the missions were quite different.

German intelligence in the Mediterranean theater was superb. The German staff knew exactly what the Allies would be doing, and they were ready. While the Allies had control of the air, and there was little fighter resistance at that stage of the war, on the ground it was different. Critical targets were well protected by Germany’s highly respected 88mm antiaircraft cannons, at the bottom of the pass and also sheltered beneath ledges along the steep mountainsides, impervious to air assault. From these ledges, the 88s would occasionally be shooting down on the B-25s after they had descended into the Pass.

As bombing relied on precise visual targeting, runs were also handicapped by weather and other natural conditions. Missions could only be effective on clear days, with minimal cloud cover or other visual obstruction. Thick clouds overhead or heavy haze trapped in the pass frequently aborted missions, especially during the cold, damp winter months.

When weather allowed, missions were usually timed for mid-day, when the sun would be directly overhead and targets along the edges of the valleys below least likely to be obscured by shadows from the ridges. Moreover, missions were flown lengthwise through the pass, from south to north, at low enough altitude to effectively see and hit the targets.

Missions usually comprised only one to four 'boxes' of six B-25s, sometimes escorted by P-51s to help defend against possible German fighters or strafe anti-aircraft positions in advance of the bomb run. The small number of bombers per mission was not only due to precise targeting and limited maneuverability in the pass, but also attrition from German resistance. After some missions, few aircraft remained airworthy for the next day.

The Germans not only knew what targets would likely be hit, but also when and from what direction the bombers would arrive, how many there would be, and at what altitude they would be flying. They were always ready, and their antiaircraft fire was accurate and deadly.

Even the greater precision enabled by the Norden bombsight came at a price. With the Norden, the pilot flew the aircraft to the point where the bombardier could lock the target in his bombsight. Up to that point, evasive maneuvers could be used to avoid flak. However, from there onwards, the bombardier flew the plane for the final two minutes of approach until the bombs were released. During that time the plane’s altitude and direction had to remain stable for the target to be hit. The bomber was then most vulnerable, and the Germans took full advantage of this vulnerability. It was, as both sides eerily agreed, “like shooting fish in a barrel.”

Nerves of steel were required for the bombardier to succeed, especially the lead bombardier. For most missions, only the lead aircraft in each box was equipped with the Norden bombsight. When the lead aircraft locked the target and eventually released its bombs, the other five planes in the box would release via either visual or radio signal, resulting in a compact bombing pattern. If the lead bombardier's nerve held and his course was maintained, those behind him would follow, no matter how fierce the resistance. And it was fierce.

Rowe once described the experience of taking off from Corsica on bright, sunny days with not a cloud in the sky. An hour and a half later, as the planes descended into the pass to approach their target, black clouds — a bit oddly, one first thought, since the sun was still shining brightly — would begin to fill the sky ahead. All were between 8000-12,000 feet, the exact altitudes of each of the V-shaped “boxes” of the bombing run, staggered 2000 feet apart. The “clouds” were the flak from the German 88s into which the planes would have to fly.

In the nose of the B-25, the bombardier was exposed, suspended over his bombsight looking down at the approaching target on the ground below. A thin cone of Plexiglas, no match at all for the flak he was rapidly approaching, was all that separated him from Eternity.

At the low altitudes of the bombing approach, the German gunners and the flashes of their 88s from the ridgesides below were clearly visible. On repeat runs to the same target, and there were many, as the Germans were superb in quickly reconstructing the facilities on which their survival depended, one could even recognize distinctive firing gestures of certain gun commanders.

Then you flew into the flak and the sky turned dark, with near-deafening sounds “like a Missouri hailstorm on a tin barn roof” as shrapnel ricocheted off the B-25's speeding aluminum fuselage.

Yet this was better than the alternative, the gut-wrenching shriek of hot metal from closer bursts ripping through the fuselage while the plane bounced violently in the explosive turbulence. Here the B-25’s durability proved invaluable; despite the high frequency of planes 'holed' by flak, most were able to limp back to Alesan or escape to Switzerland even with parts of wings, half the rudder or other parts gone or inoperable. The B-25’s ability to stay in the air despite heavy damage sometimes defied the laws of aviation.

Almost miraculously, throughout the Brenner campaign only 46 aircraft were lost, though more than 10 times that number suffered 'significant' holing and were no longer airworthy without reconstruction.

While planes may have survived, crew members too often didn’t. The B-25 normally had a crew of six: pilot, co-pilot, bombardier/navigator, radioman, engineer, and tail gunner. The radioman and engineer doubled as turret and waist gunner. For the lead plane of a box, there was a dedicated navigator in addition to the bombardier.

Especially exposed, in addition to the bombardier, were the top ball turret gunner, the waist gunner and the tail gunner — all of whose Plexiglas compartments protruded from the fuselage with little protection from the flak. An aircraft’s crew could change frequently as a result, and due to the shortage of trained airmen, those who survived were kept on duty ever longer, with more and more missions being flown.

Adding further to the strain on the four squadrons of the 340th were several inexplicable events. Twice during the fall of 1944, the six planes of a box took off safely and rose toward cruising altitude through peaceful cloud banks. Less than a minute later, when they emerged from the clouds, only five planes remained. In each case, the sixth plane and its crew simply vanished, with no trace ever found. It was not only the enemy or forces of nature against which crews had to prevail, the risk of these at least being calculable, but seemingly fate itself.

Among Rowe’s 488th squadron mates had been fellow bombardier Joseph Heller, whose novel Catch-22 drew upon the unit’s experience. While many unit veterans did not appreciate the unflattering view the novel gave of military logic and bureaucracy, it was based on all-too-real events: the death of the gunner whose remains were washed out of the remnants of his turret with a fire hose; the ditchings at sea by fatally holed aircraft on the return trip to Corsica; planes and crews which simply vanished; the continual raising of the number of missions required before the crewmen could be relieved; the sheer irrationality of flying day after day directly into the German flak; Rowe, Heller and their squadron had lived through and remembered all of these.

Or to be more precise, they were unable to forget them.

While crews would differ between the men and aircraft airworthy for the day, each plane had a unique identity. Planes were marked on their twin stabilizers with an “8” for the last digit in “488th” plus a distinguishing letter. Joseph Heller flew in 8P; Kenneth Rowe flew in 8R; Francis Yohannon, the model for Heller’s fictional character “Yossarian” in Catch-22, flew in 8U. Yohannon, similar to “Yossarian,” flew a total of 66 missions (in other theaters 25 would have completed one’s tour of duty).

When not flying, the crews ate, slept, swam, played softball or volleyball on fields near their tents, awaited the next day’s mission, and otherwise whiled away the time. Rowe sketched the local flora and fauna; Yohannon played with his pet cocker spaniel; Heller wrote.

The men of the 488th returned from the war in July 1945, the Brenner Pass having been denied to the enemy; the war won. Rowe and Yohannon went on to become career officers; they met frequently at reunions of the 488th and the 340th Bomb Group; both retired from the Air Force with the rank of Lt. Colonel.

After retirement, Rowe returned to his previous career in biology and conservation; Yohannon, who died in 2001, lived his remaining years quietly with his family. Heller, who died in 1999, became one of America’s most famous writers, with his Catch-22 ranked number 7 on Modern Library’s list of the best novels of the 20th century.

Life can have strange twists. Nearly 20 years after the war had ended, Kenneth Rowe was back in Europe with the Air Force, having been posted to Germany to administer the European branch of GEEIA, the Ground Electronics Engineering Installation Agency which had been initiated by his friend and colleague General Curtis LeMay. One day Rowe was talking with a German engineer with whom GEEIA had contracted. Suddenly each realized they had “met” before: during the war the German had been a military engineer in the Brenner Pass, tasked with rebuilding the bridges Rowe and the 488th had been bombing.

They paused and looked at each other for a long moment.

And then moved on, each with the same wish: that never again would anyone need to endure the experience they both had survived.

John D. Hopkins is a nephew of Kenneth C. Rowe.

Sources: Conversations with Kenneth Rowe and the Rowe family archives, as well as personal histories of crews of the 57th Bomb Wing, 340th Bombardment Group, and 488th Squadron. B-25 photos courtesy of the 57th Bomb Wing website (see more images here and here, and also Doug Cook's Google Earth simulation of a B-25 bombing run in the Brenner Pass).